Safety, service, security, sustainability, and now sanitation!

Since the dawn of the Jet Age, the very first priority for airlines has always been to keep passengers safe. And that is still true today. But the priorities of airlines have evolved over time.

Before Southwest Airlines invented the low-cost carrier model, airlines were always competing on who could provide the best service, as travelling by air was a privilege only the wealthier part of the population could enjoy. While some may argue that service has been in decline for the past many years, the service element will always be the most powerful way to influence customers, especially providing good customer service when things do not go as planned.

Post-9/11, security became much more of a priority for airlines and airports. JetBlue was the first airline to install bulletproof cockpit doors across their fleet, Air Marshalls were introduced on flights in the US, all bags and passengers were carefully screened, and the TSA (Transportation Security Administration) was born.

Lately, or at least before the coronavirus elbowed its way in like a middle-seat passenger fighting for the armrest, we have seen airlines focus increasingly on sustainability, by modernising their fleets, using carbon offsetting schemes, reducing or eliminating plastics onboard, and substituting oil-based jet fuel for SAF (sustainable aviation fuel).

While all of these priorities still matter and will continue to matter going forward, there is a new sheriff in town, and he too is here to stay. Enter the age of sanitised travel. Will this new age mean the end of the in-flight magazine?

It’s all about reassurance

As it happened after 9/11, where passengers needed to be reassured that it was safe to fly from a security standpoint, so it is now, but with sanitation being at the forefront of passengers minds. Many of the reassurance efforts we see airlines taking are therefore also to provide visual cues to passengers that they are actively doing something to keep them safe from the virus.

Reassurance can be defined as a special kind of education that counteracts fears. Reassurance relieves or removes unnecessary anxiety, especially regarding one’s physical or emotional health. Barton D. Schmitt, in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics (Fourth Edition), 2009.

Although this quote comes from a Pediatrician , which evidently has nothing to do with flying, there is some basic psychology at play here. After all, people are emotional beings, and in this situation where there is information overload, the fear of doing almost anything, let alone fly, is spreading faster than the virus itself. Unfortunately, that is why airports and airlines are taking more extreme measures in the initial stages and immediate aftermath of this crisis, as they did post-9/11.

Something new, something borrowed, something…missing?

We recently released a report called “The Rise of Sanitised Travel“, where we highlighted 70 touch-points/areas throughout the customer journey that are likely to change post-corona. Some of these areas will see completely new processes, procedures and products introduced. Some touch-points will be modified, and methods will be borrowed from other industries to adapt it to air travel. Moreover, we might even see some things that we associate with air travel, just simply disappear.

On a recent reparation flight from India to Canada, our founder and CEO, Shashank Nigam, set out on a journey with his family that revealed a lot of the realities that airlines and airports have to deal with in the post-corona world of air travel. Their journey took them onboard 2 airlines (Qatar Airways and Air Canada) on 3 flights, and through 4 airports (Mumbai-Doha-Montreal-Vancouver), and it quickly became clear that there were no consistent hygiene and sanitation measures in place, as both the airlines and airports had their own sanitation procedures and practices.

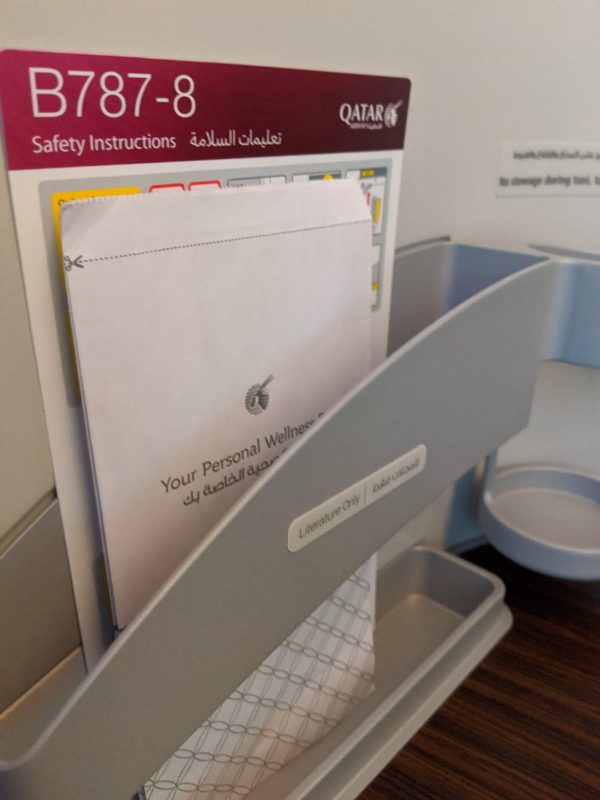

As a matter of fact, there was only one thing that proved consistent throughout the entire trip: the printed inflight magazine was missing.

Air Canada: The seat-back pocket is empty, except for the safety card.

Qatar Airways Literature Holder

Going digital

In an attempt to minimise the risk of spreading the virus from one passenger to another, removing the inflight magazine, and other literature from the seat-back pocket seems to be a rather sensible thing to do. And in this digital age, where many airlines are equipped with W-Fi, inflight entertainment systems, and travellers often carry 2 or more devices onboard, the case of making the inflight magazine a digital publication only, it seems like a no-brainer.

Airlines like KLM, Brussels Airlines and Finnair have already offloaded their printed inflight magazines in 2019, in favour of a digital version. Digital versions also make it easier to track what content receives more attention, and thereby tailor marketing messages to make them more relevant. Going digital would help the sustainability agenda that most airlines are pursuing, and Brussels Airlines have estimated that they can reduce CO2 emissions by around 35 tones per year, across their 250 daily flights, or 90.000 flights per year.

Crunching numbers – Emissions, Costs and Revenues

American Airlines, the largest airline in the world, with a current mainline fleet of 871 aircraft, have nearly 137.000 individual seats across their fleet, all of which are equipped with an inflight magazine. And if we count the American Airlines Group (American) total fleet size, meaning we add American Eagle’s fleet of 579 regional jets, the total seat count jumps to 171.000. According to Ink, which produces inflight magazines for 35 airlines across the world, one of them being American Way for American Airlines, they can produce up to 1 million copies during busy months for the airline.

As I personally enjoy reading the inflight magazines, I also sometimes bring them home with me. And as it turns out, I happen to have a copy of the July 2019 version of American Way, that I saved from my trip last summer. I also happen to have a very precise scale at home, so I decided to do some number crunching. Stay with me.

Sustainability

This magazine weighed 275 grams and had a total of 162 pages. And with 1 million copies in distribution during the busiest months, such as the July issue which I have, that is equivalent to 162 million pages, weighing in at a total of 275 tonnes. But not all of these magazine fly, as many are also found in lounges and at other touchpoints.

So how many magazines fly? It is rather difficult to say, as it varies a lot based on the aircraft type, and how many legs the aircraft in question flies per day. American claim to operate 6700 flights daily, at least they did so before COVID-19.

As we can assume that there is 1 magazine per seat, at any given time, we should calculate the total number of individual seats that American has across its fleet, multiplied by the weight of 1 magazine, to find out what extra weight American Airlines is actually flying around with. So here goes:

171.000 seats x 275 grams = 47 tonnes.

American has a total fleet of 1450 aircraft, and with 6700 daily flights, that comes out to 4.6 flights per aircraft per day. 51% of the fleet consists of narrow-body aircraft with an average of 164 seats per aircraft = 46 kg in inflight magazines. 9% are wide-bodies with an average of 270 seats per plane = 74 kg in inflight magazines. The remaining 40% are regional jets with an average of 68 seats per aircraft = 19 kg in inflight magazines.

Let’s assume that each aircraft in the narrow-body fleet operates 4 legs per day, the wide-body aircraft 1.5 legs per day, and the regional jets 6 legs per day. That comes out to nearly 6650 legs per day, so very close to the number of daily flights that American claims to operate. In other words, 45% of daily legs are operated by the narrow-body fleet, 3% by the wide-body fleet and 52% by the regional jet fleet.

Finally, we can now calculate an educated estimate of the additional weight that American actually carries around every day, from inflight magazines, by aircraft type, by multiplying the number of daily legs per aircraft type, with the additional weight per leg.

- Narrow-bodies: 2980 daily legs x 46 kg = 137 tonnes

- Wide-bodies: 186 daily legs x 74 kg = 14 tonnes

- Regional = 3474 daily legs x 19 kg = 65 tonnes

- Total added weight per day across the fleet =216 tonnes.

On an annual basis, American would then fly an additional 79.000 tonnes of inflight magazines around. For perspective, that is equivalent to about 3% of American’s annual cargo tonnage capacity, which is around 2.34 million.

From a CO2 emissions perspective, and if we use the numbers that Brussels Airlines have calculated (although their fleet composition is quite different), we can roughly estimate that inflight magazines contribute to an additional 2.57 kgs of CO2 emissions per flight. Which in the case of American Airlines would amount to 6.28 million tonnes of CO2 emission annually (Based on operating 6700 flights daily or 2.4 million flights annually).

Costs

In an article from National Geographic, which outlines the results of a study from two aeronautical engineers from MIT, it is found that the added fuel cost of carrying an inflight magazine weighing 0.6 pounds (Ca. 275 grams), on one plane over one year is $18,8. The example uses a Boeing 737-800 operated by United Airlines, but if we assume the same numbers apply to AA, without taking into account the changes in fuel cost since the study was done, the variances in short vs. long-haul flights, and seasonality, this would mean a total additional fuel cost of $215.000 per month, or close to $2.6 million per year.

Revenue

One of the reasons that airlines are most likely not so keen to get rid of their inflight magazines, is because it ultimately is a source of revenue. Again, using the largest airline in the world as an example, I fine-combed my American Way July 2019 issue, and counted every ad, and its placement, and cross-referenced it with Ink’s rates, which are publicly available.

The July 2019 issue contained 88 ads, of which 50 were full pages ads. Using the average list prices, and multiplying it with the number of equivalent ads, the calculations indicate that Ink, in behalf of American Airlines, supposedly had revenues in the range of $6 million for the issue in question. However, I know from my experience of having previously done research within this space together with another airline, that advertisers never pay rack rates and nearly always receive heavy discounts for various reasons. Therefore, it is very unlikely, if not certain, that Ink had revenues of anywhere near $6 million, despite the July issues being one of the best selling issues. To make it even more difficult to estimate potential revenues for the airline, each issue varies in size, as well as the number of ads sold, and of course, Ink also takes a cut from AA’s revenue, so it is safer to say that the revenues generated from inflight magazine ads help remove the burden of the fuel costs for the airline.

A paper perspective

In an interview I held with the CEO of Ink, Michael Keating, he said that the removal of inflight magazines is just a temporary measure. He added that he has had no conversations with airlines wanting to stop the production going forward.

In March, most airlines did not remove the inflight magazines, although they did not replenish them. In April, many airlines decided to not place their inflight magazines onboard, both because it provided a visual way for passengers that they were doing something to keep them safe, and also because removing them makes it much easier and faster to clean the seat-back pockets and the aircraft in general. But in May, airlines like American Airlines, have put their American Way inflight magazine back where it belongs.

Pointing to a recent study done by the Laboratory of Virology, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Hamilton, MT, USA, Ink claims that

“Paper is one of the safest surfaces in the sky.”

According to the study, passengers are almost twice as likely to contract Covid-19 from touching the armrest, window blinds, lavatory door, tray table overhead bins, IFE screen or credit card machines.

A day in the life of an inflight magazine

In their Clean & Green presentation, Ink provides an example of how the virus may transmit onboard during a daily cycle. Based on an 80% load factor, an 80% pickup rate of magazines, and short-haul frequencies of 6 flights per day per aircraft, statistically, there are 3.8 x 20-minute reads per day per seat. Based on a 16-hour operation of the aircraft per day, we can assume there is 4.2-hour gap between each read of each magazine. On average, and statistically, this means a magazine could only pass the virus on to one other person as, by the third reader, the virus would no longer be transmissible. Unlike the rest of the aircraft surfaces, every night during the downtime of the aircraft, it would self-sterilise. The risk is 5x greater when compared to a plastic armrest, table or even the laminated safety card from the first flight of the day.

An important communications channel

When you step on board an aircraft, you will to some degree find yourself limited and restricted, in terms of what you can do stay entertained. The inflight magazine is a way for airlines to communicate with its passengers, through its own content and thereby control the narrative. It has engagement rates of up to 26 minutes, which is substantially higher than other digital channels onboard, such as the IFE system, where most of the content is not made by the airline, but airlines in a sense are giving away their captive audience to someone else. As showcased earlier, it is also a revenue stream, which allows the airline to promote brands that are in-sync with their own brand, which in turn can reinforce their positioning in the market.

Can you only read an inflight magazine, inflight?

Some airlines, like SAS Scandinavian Airlines, make their digital inflight magazine available on their app 24 hours before departure. This allows the passenger to engage with its content before the flight, and increases the potential exposure to passengers, making it a more interesting proposition for advertisers to feature in the magazine as well.

A clever approach, which has been taken by Qantas Airways, is to simply print and send their inflight magazine to frequent flyers. This also seems like a more sustainable solution, both from a carbon and economic perspective, as sending a magazine to someone’s address, all things being equal, is a cheaper and less carbon-intensive way to distribute it.

So, is there a future for the printed inflight magazine?

It depends. At the end of the day, it is up to each airline to do what makes sense for them, as all airlines are different and serve different markets, with different preferences Taking all aspects into account, some airlines might decide that now is the perfect time to go all-digital, to position themselves as being extra clean, cut costs and become more sustainable. Whereas for others, the preference for the paper will continue to prevail, as they see a strong communications channel and formidable revenue stream.

What do you think will happen to the printed inflight magazine?

SimpliFlying has set up a Rapid Response Team to help airlines be ready for post-corona travel’s realities. The team has been holding Board-level briefings to orient executives with the new touchpoints. We will be happy to do a 30-minute call with your executive team to run through the detailed post-corona customer journey map. In order to help the industry, these calls are free for airlines and airports. Get in touch to set up a call.